The Woman in Black is a fine and appropriate return to atmospheric horror movies for the once great Hammer Films. It sticks to the source material’s (the 1983 novel by Susan Hill) original time period (the late 19th century to the early 20th century), with authentic costumes, sets and a spectacularly creepy haunted house. The mood is perfect (emphasized by extreme isolation), the sustained dread is gut-wrenching, and the anticipation is a killer. Although this is a ghost story with the standard dilapidated, abandoned mansion as the central location for trepidation, it presents several very unique ideas for old-fashioned hauntings.

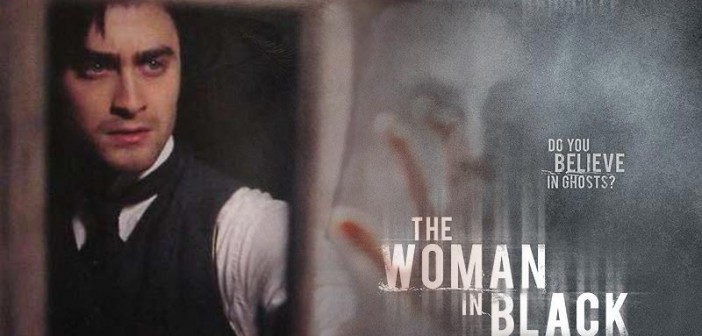

Young Arthur Kipps (Daniel Radcliffe) lost his wife (Sophie Stuckey) during childbirth a few years ago. He frequently has visions of her in her wedding dress (symbolically, the woman in white), which gives him a newfound sense of spiritualism, but hampers his ability to work effectively at the law firm that employs him. His last assignment, one that is necessary to prove his dedication to the company as well as demonstrate his recovery from grief, is to journey to a remote village on the outskirts of England. Once there, he must sort out the papers left at Eel Marsh House to finalize the financial and legal dealings of the recently deceased Mrs. Drablow. Although the townspeople wish for Kipps to leave as swiftly as he arrives, he finds a friend in Simon Daily (Ciaran Hinds), the only man in town with a car, and one who has lost his son in an accident and whose wife (Janet McTeer) has gone crazy with mental suffering. What is supposed to be a simple job becomes plagued by disconcerting secrets, the mysterious deaths of children, and the unnatural sightings of an ebony-veiled woman in black funeral attire.

The use of demonic-looking toy contraptions and unnerving dolls is nothing new. Nor are the expected, manipulative jump scares fueled by loud thuds, screeches, and jarring sound effects (and a pesky crow), or the sudden appearances of otherworldly imagery coupled with crescendo-favoring musical accompaniment. But the evil spirit itself is wonderfully singular in its ability to scare through subtle materialization (coming into sight in alarming manner, with slower paced emergences more traumatizing than the rapid ones), its targeting of children and pattern of avoiding physical harm to adults, and most of all in its vengeful mission that cannot be appeased, calmed or quelled. She’s a wronged poltergeist of legendary ill-omen stature, foreshadowing doom; she’s not meant to be satisfied but rather endured.

The explanation for the wraith is much more straightforward and understandable than in the previous film adaption. The many questions that arose from the 1989 version are neatly covered here, opting for a clear-cut motive of insatiable revenge. Kipps still possesses an uncanny bravery (or stupidity) in the face of genuinely frightful, spectral harassment, and attempts many panic-induced, pointless parries (such as locking the door on a ghost). The conclusion has changed, along with the previous unforgettable climax, but despite the morbid nature of the story and the terminal confrontation, screenwriter Jane Goldman (or perhaps interfering producers) has chosen the most assuaging method to wrap up a dark narrative of eerie tragedy and undying wrath.