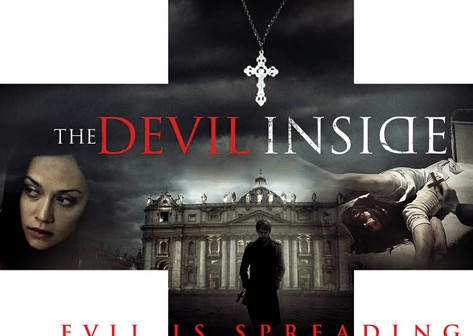

Back-Alley Exorcisms

The Devil Inside is the first demonic possession film I know of to entertain the idea of back-alley exorcisms – that is, those performed by ordained exorcists outside official religious jurisdiction. They’re portrayed as progressives eager to bypass the hypocritical and bureaucratic sanctioning of the church, which, according to them, has been alarmingly selective when it comes to who can and cannot receive the services of an exorcist. Officials stipulate that there’s a definite difference between possession and mental illness, and not all cases fall into the former category. The priests in this film understand that there’s a definite difference, although they also believe that a great many people are authentically possessed and have been overlooked by the system. And so, under constant threat of discovery and excommunication, they provide help to those who need it.

On the basis of the film’s pathetically low Rotten Tomatoes score, I would wager that most critics somehow missed this surprisingly clever and timely social commentary. It seems we’re also in disagreement over how frightening the film is. While by no means the scariest movie ever made, it effectively builds tension, and there are moments that made me jump in my seat. Is it just that I scare too easily, or did I remember how these movies are supposed to work? Furthermore, there’s something to be said about a demonic possession movie that doesn’t hold back in terms of disturbing visuals; in the course of this movie, we will see people contorting into impossible shapes, splayed bodies at a crime scene, and in one instance, profuse vaginal bleeding. The only time I thought the filmmakers went too far was in a scene that, oddly enough, did not involve an exorcism. Instead, it involved a baptism.

Having said all that, some of the criticisms aimed at this film are valid. From a technical standpoint, it breaks no new ground as a found-footage mockumentary, at this point a genre in and of itself. We have the usual fare: The combination of handheld and surveillance recordings, the persistent use of the Queasy Cam, the frantic journeys through dark corridors and rooms, and the bookending claims that (1) the film is documenting a real event, and (2) the case remains unsolved to this day (we’re even provided with the address of a website to visit for more “information”). Structurally, it gets off to an implausible yet decent start, only to become more predictable and routine as it enters the final act. Initially engaging characters become progressively less developed until they’re reduced to stock horror movie caricatures. And then there’s the ending, which isn’t bad so much as it is abrupt. When the credits start rolling, there’s the unshakable feeling that something more needs to be said.

The film opens with a recording of a 911 call made on October 30, 1989, in which we hear the emotionally vacant voice of a woman slowly confessing to the murders of three people. We then see police footage of the crime scene, and yes, we get ample views of three gore-ridden bodies and the blood-stained weapons used on them. The victims, we soon learn, were trying to perform an exorcism on the murderer, a woman named Maria Rossi (Suzan Crowley). After being arrested, the Catholic Church got involved and shipped Maria off to a sanitarium in Rome. The details of the America-to-Italy transfer are a little sketchy, as is the reason for having her sent to Italy at all, but never mind. At this point, we flash forward to footage shot in 2009. It seems that Maria’s daughter, Isabella (Fernanda Andrade), has hired a documentary crew to follow her to Rome and capture on film the attempts to save her mother.

After attending an exorcism seminar, she’s introduced to two priests, both ordained exorcists. One is Ben (Simon Quarterman), a Brit who entered the priesthood largely due to his uncle. The other is David (Evan Helmuth), an American who’s also a licensed physician and has built his reputation on the fusion of science and religion. While both are men of faith, they disapprove of the church’s dismissal of certain possession cases, and they take it upon themselves to perform the necessary exorcisms – a big no-no. They make it clear that, in order to really understand demonic possession, Isabella will have to witness an exorcism first hand. And so she does. She will also reunite with her mother, who becomes dangerously hostile at the sight or even the mere mention of religious paraphernalia. The only exceptions would be the inverted crosses she has cut into her forearm.

That all of this is ridiculous, there can be no argument. All the same, the characters were developed in such a way that I was genuinely curious about where the story would go. Alas, the Maria Rossi subplot is eventually dropped altogether, at which point the film stops being character-driven and becomes a run-of-the-mill horror thriller. Ideas that were only alluded to, such as multiple demon possession and the transference of a demon from one body to another, are now foremost on the minds of the filmmakers. Given the deceptively satirical undertones of its opening and middle acts, this is a bit of a letdown. All the same, The Devil Inside is nowhere near as bad as most claim it is. If you can see your way past its lack of originality and authenticity – which is, when you think about it, the case with most horror movies – I think you’ll be plenty satisfied by what it has to offer.